Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles

Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles

Sierra Leone’s army also came under attack from the Revolutionary United Front (RUF) that was led by the country’s former army corporal Foday Sankoh, who was collaborating with the Liberian rebels.

The resulting civil war left over 50,000 people dead. It has been reported that civilians were subject to horrific acts of mutilation, including having their limbs, ears, and lips cut off.

Incidents of rape and forced labor were widespread, and many civilians were used as unwilling human shields or held in captivity and subjected to repeated acts of sexual violence by the combatants.

Once captured, boys the age of Charles were trained to shoot, to loot homes, to burn houses and to commit other atrocities against civilians.

(Story continues below)

Charles told ACI Africa that two things saved him from bending to the demands of his captors.

Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles

Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles

“Many boys willingly accepted to work for the rebels. Most were excited to hold the gun for the first time. Others were big and easily fit into the rebel groups,” he said, and added, “At nine, I was very tiny. But most times, I pretended to be a slow learner in handling the gun. I never wanted anything to do with killing people.”

He says that he tried to escape several times but was always captured and taken back to be trained to fight. The last time he was captured was in 1995 when he was 14 years old. This time he faced mutilation for having attempted to flee in the company of other boys.

Charles says that he was in a long queue of boys who were losing a limb each as punishment for their misconduct when a military plane swooped in, causing confusion and giving the boys the opportunity to flee. Some boys lost their limbs but Charles was among those who managed to escape unscathed.

When the Sierra Leonean conflict ended in 2002, Charles went back to school without having undergone any formal psychosocial support.

Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles

Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles

“I harbored terrible memories of what I had witnessed even as I went back to school,” he said, and added, “My mother and I agreed that I could never say anything about what I had seen in the war. She thought that for me to move on with my life, everything about me being a child soldier was to be buried in the past. My mother feared that I would be stigmatized if I shared what I had gone through.”

Charles says that the first time he shared his experiences as a child soldier was with a Catholic Priest some time in 2012. It was the Catholic Priest who encouraged him not to shy away from his past, noting that his story would be an inspiration to people undergoing difficulties.

“Today, I can freely talk about my childhood experiences. I am even working on a book that will have everything about my years as a child soldier and my life after the war,” he told ACI Africa January 14.

Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles

Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles

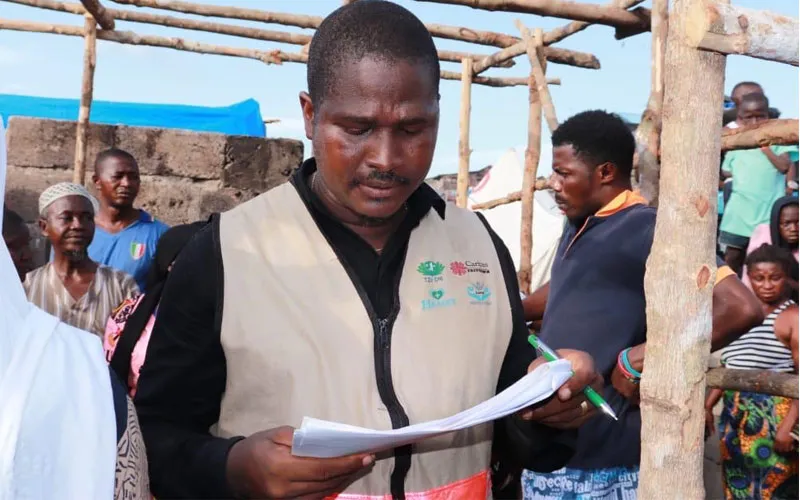

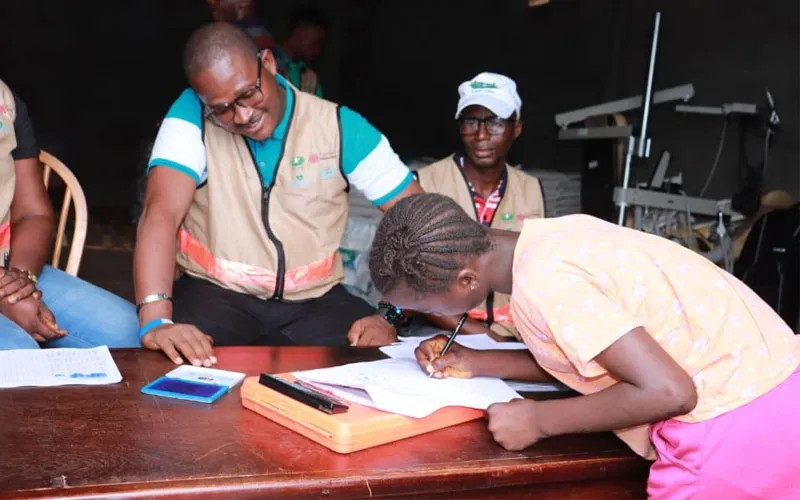

The 38-year-old who works as Caritas Freetown’s Programs Manager told ACI Africa that many former child soldiers are still walking around with daunting memories of what they saw and did.

“Child soldiers in Sierra Leone were not properly re-integrated into the society. The children who spent many years being taught how to survive in the jungle have not been taught how to survive where there is no conflict,” Charles says.

He adds, “Child soldiers were taught how to use the barrel to get anything they wanted. They were taught how to loot, how to give commands and how to sleep with anyone they wanted. Today, they don’t know how to work hard for their living, how to buy clothes and how to get married.”

He says that Sierra Leone’s National Committee for Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration (NCDDR), which was formed to equip former child soldiers with skills to survive in the current realities has failed to deliver on its mandate.

Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles

Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles

“The disarmament program did very little to help former child soldiers. It was a three-month technical training program after which they were given tool boxes to start businesses. A good number of them sold the tool boxes and went back to their previous lives,” the Caritas official said.

He added, “The program could have been planned and executed in a better way. It should have been fashioned to address various kinds of gaps in the lives of former child soldiers. They are not just economic gaps. There are also psychosocial needs that cannot be handled in just three months.”

Charles has researched widely on peace and development during his studies in Sierra Leone and at various international higher learning institutions including Manchester University in the United Kingdom. He has also advocated for reforms in the country while he worked at the Centre for Coordination of Youth Activities, an organization that works for youth empowerment.

In addition to his campaign roles at the Sick Pikin Project and at Caritas Freetown, Charles oversees various development projects at the Healey International Relief Foundation as the organization’s In-Country Manager.

Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles

Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles

Started only in 2018, the Sick Pikin Project has managed to raise enough funds to send 74 children who had various complicated health conditions that required complex surgeries abroad. The children have been treated in hospitals in India, Spain and Italy. Another 126 children have been treated in hospitals in Sierra Leone through the project.

In the January 14 interview with ACI Africa, Charles said that the Sick Pikin Project fulfills a dream he harbored as a child.

“I always wanted to be a doctor. But I didn’t become one. Somewhere at the height of the activities of the Sick Pikin Project, I realized that I was bringing some form of healing to the children from poor families. I realized that I didn’t have to become a doctor to participate in God’s divine healing,” he said.

Charles told ACI Africa that he is a father of 18, most of them adopted.

Taking care of many children is his way of giving the young ones a childhood he says he never had.

He shares that he is also a mentor to two former child soldiers, and explains, “My biggest lesson in life has been to be the trusted confidant for anyone in difficulty. I have been in a dark place myself and I know the plight of child soldiers. I believe that I can help them to overcome their fear. But I first have to be their trusted confidant.”

Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles

Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles

In his circles, Charles has Fr. Peter Konteh, the award-winning Sierra Leonean Priest who co-founded the Sick Pikin Project and is also the Executive Director of Caritas Freetown and Acting Director, Caritas Sierra Leone.

Charles describes Fr. Konteh as a father and a mentor, saying, “He has put a lot of trust and confidence in what I do. There are times that I get depressed and Fr. Konteh is always there as a loving father and my counsellor. He has helped me grow in the past 13 years we have been working together.”

He says that the nomination for the 2022 African Genius Awards, which recognizes individuals who have contributed to the development of their countries through activism, business or literature, cements the trust that people have in the organizations he represents.

“The nomination means a lot to me. Our efforts are being seen and recognized and as we run a project that survives only from goodwill actions from kind hearted individuals, it is significant to bank on public trust that is bestowed on us because of the work we are doing. Therefore, this award will not only recognize our work but add value to what we do and help us reach more and more people,” Charles told ACI Africa.

He added, “Being recognized all the way from Southern Africa when I am from West Africa also means that more is yet to come.”

Agnes Aineah is a Kenyan journalist with a background in digital and newspaper reporting. She holds a Master of Arts in Digital Journalism from the Aga Khan University, Graduate School of Media and Communications and a Bachelor's Degree in Linguistics, Media and Communications from Kenya's Moi University. Agnes currently serves as a journalist for ACI Africa.

Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles

Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles

Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles

Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles

Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles

Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles

Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles

Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles

Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles

Credit: Ishmael Alfred Charles