He shares that many of his siblings were killed in the 11-year Sierra Leonean civil war that broke out in the provinces, leaving behind a trail of destruction in his village.

Fr. Fillie recalls being attracted to Fr. James Ward’s sophistication when he decided to go and live with him.

“What I admired most about Fr. James Ward was his English language, which I found to be very sophisticated. He also brought all the children gifts when he came to celebrate Mass,” he said, adding that one day, he begged to go to the Parochial house where he clung to the Irish Priest and refused to go back home.

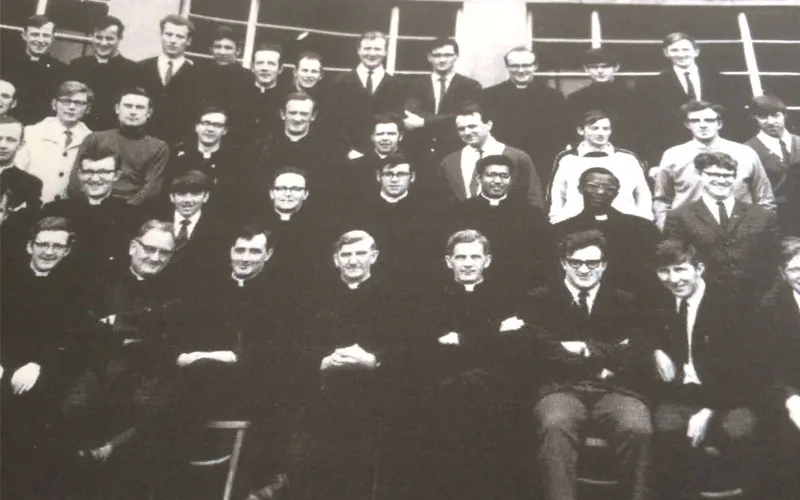

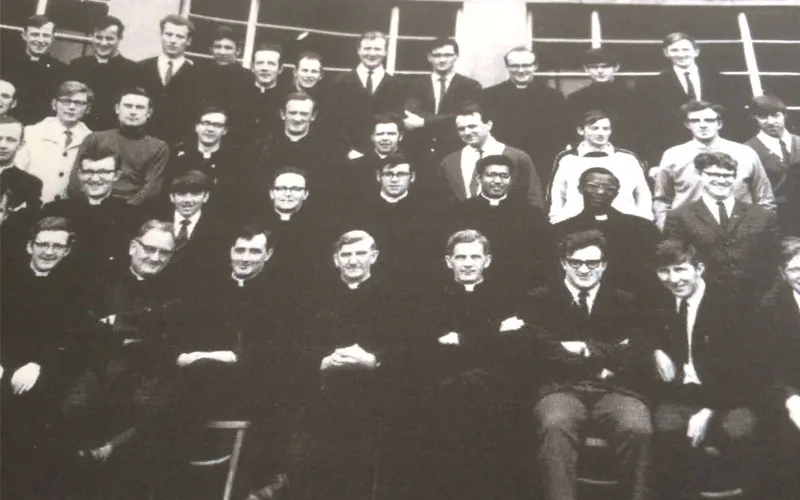

Credit: Fr. John Michael Fillie

Credit: Fr. John Michael Fillie

His father’s efforts to take his back were futile. He insisted that he wanted to learn the English language.

(Story continues below)

One day, Fr. James Ward was transferred to Ireland, and the young boy had to go back home where he was enrolled in school and proceeded to learn Arabic. His father and the entire household had become Muslims.

Young Fillie was delighted when one day, Fr. James Ward who was visiting his school spotted him and enticed him with the idea to enroll in catechism.

His father, a staunch Muslim, was immediately opposed to the idea, Fr. Fillie shared, and added, “I had to learn catechism in secret. I was baptized in 1954 and given a Christian name behind the back of my family.”

Fillie’s fondness for Christianity did not however mean that he had plans to become a Priest. He shares that he disliked the idea, and it took lengthy convincing by his tutors in Secondary School, to have him join the Seminary.

“I wanted to pursue a course in Agriculture because farming was all my village engaged in. I applied to one prominent Agricultural College in Sierra Leone and took an entry examination,” he says.

However, a Priest who taught at the secondary school broke the news to Fr. Fillie that he and five other boys had been selected to join the Seminary in Nigeria.

Young Fillie shared the news with his uncle who encouraged him to go to the Seminary.

“I was devastated,” Fr. Fillie shares about being encouraged to become a Priest, and adds, “My uncle was the most educated member of our family and I knew that his word was final, no matter what my father said.”

Fillie pursued a course in Meteorology and worked as a meteorological observer at an airport in Sierra Leone, hoping to convince everyone that he was not interested in Priesthood.

He resigned six months later and traveled to Nigeria to join the Seminary in 1965 where he completed his Novitiate.

Later, when the Nigerian civil war broke out in 1967, he was flown to Ireland where he completed his formation. He was sent back to Sierra Leone for his ordination on 20 June 1971.

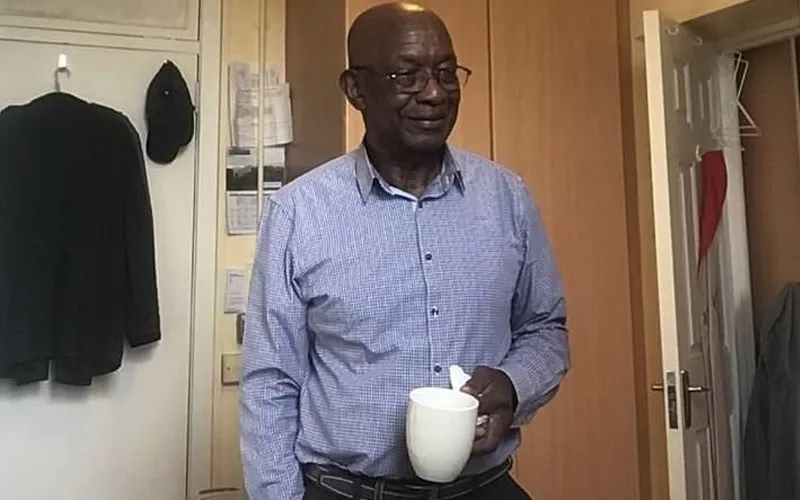

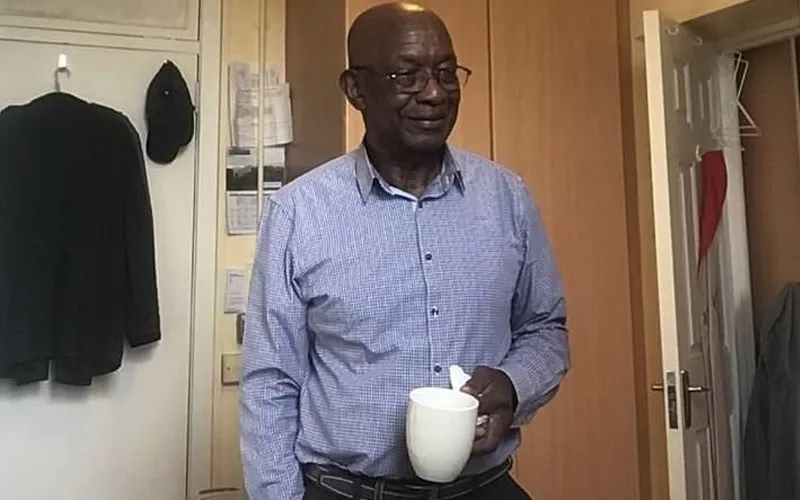

Fr. John Michael Fillie at St. Mary’s Nursing Home & Hospital, Phoenix Park, Dublin. Fr. Fillie worked at the Hospital as the Catholic Chaplain from 2013 to 2021 before he was advised to retire because of his advanced age and the COVID-19 outbreak. Credit: Fr. John Michael Fillie

Fr. John Michael Fillie at St. Mary’s Nursing Home & Hospital, Phoenix Park, Dublin. Fr. Fillie worked at the Hospital as the Catholic Chaplain from 2013 to 2021 before he was advised to retire because of his advanced age and the COVID-19 outbreak. Credit: Fr. John Michael Fillie

Following his Priestly ordination, Fr. Fillie went to several places, combining pastoral work with his teaching ministry in Spiritan formation.

All through the 11-year Sierra Leonean civil war, Fr. Fillie remained in the country, risking his life to give hope to hundreds of thousands of people who had been displaced by the war, the amputated, and those who were on the verge of starvation in camps that had sprung up all over the country.

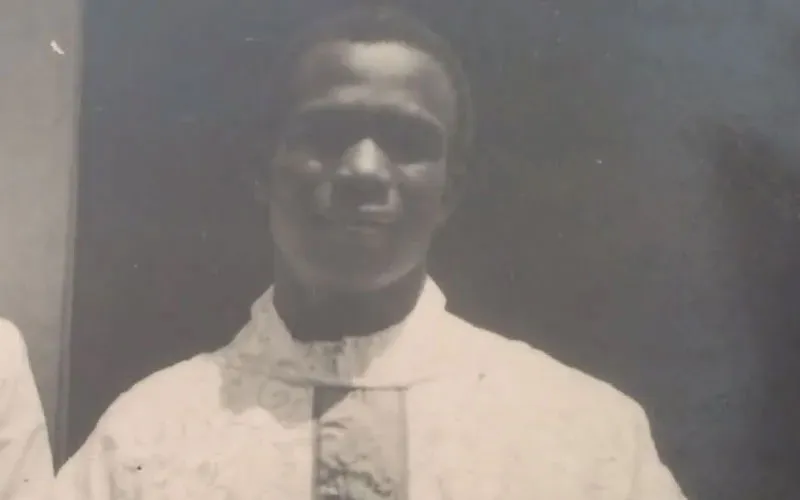

Where he had no desire to become a Priest, his calling became clearer to him when he saw the joy that his ordination brought to the locals.

“I soon realized what a huge responsibility I had as the first Missionary Priest in the whole country, and certainly the first Priest among the Mende, my tribe. I saw the joy in their eyes. I became the Vocations Director for my Congregation. I became very cautious of my responsibility. And now, the Holy Ghost Fathers Congregation is very respected in Sierra Leone,” the Spiritan Priest says.

Serving as one of the few Priests in the entire country, Fr. Fillie sometimes outworked himself and suffered burnout. Once, in two straight weeks, he drove from Sierra Leone’s capital Freetown to Njala Komboya, a remote village in the Diocese of Bo, and all the way to a meeting near the Liberian border.

He then drove back to the East to Kailahun near the Guinea border, then to Yengema in Kono District, then back to Freetown. All the while he was talking to people, attending meetings, and celebrating Holy Mass.

“At the end of the two weeks, I was exhausted. I decided to go to Freetown to rest. On my way, I had a nasty accident and lost consciousness. I screamed when I woke up to find myself surrounded by white people. I had been flown from Sierra Leone to London for treatment. I went back to Sierra Leone after recovering and was soon sent to celebrate Mass at a Primary school in Freetown,” Fr. Fillie shared with ACI Africa.

At St. Edwards School in Freetown, a young Altar server who could not break his gaze from Fr. Fillie’s big scar on his forehead immediately decided that he would become a Priest to help the injured Priest in his ministry.

“The young boy was so upset to know that in my state, I still had to go to class to teach and to celebrate Masses. He told me that he wanted to become a Priest to help me. I followed up with him. He is now a Priest of the Archdiocese of Freetown. His name is Fr. Konteh,” Fr. Fillie said, referring to Fr. Peter Konteh, the Executive Director of Caritas Freetown.

Fr. Peter Konteh. Credit: Caritas Freetown

Fr. Peter Konteh. Credit: Caritas Freetown

In war, Fr. Fillie says, he saw the immense suffering of the people and that gave him more conviction to stay in Priesthood. “There are times I thought of quitting, especially when I saw how the war erased the work of the missionaries. All of my confreres fled from Sierra Leone and I was left all alone. I can’t blame them because there was a lot of hostility directed to the men of God.”

Asked how he survived the hostility from the rebels, Fr. Fillie recalls, “Every day I went out to do pastoral work was a risk I took. I counted on the protection of some of my former students who had joined the rebel forces. They had immense respect for me. And word went around that I should be protected.”

“The military protected me, and the rebels protected me as well. The civilians made it their business to see that I was well taken care of. But there were many times I narrowly escaped killing when I was harassed at checkpoints. It was always a matter of risking,” he further recalls in the March 28 interview with ACI Africa.

When schools were ordered to close at midday as violence swept through the provinces, Fr. Fillie organized volunteer teachers who helped to keep thousands of children in school in the afternoon hours. This he did to keep as many children as possible from being recruited by the rebels.

The Spiritan Priest also went knocking on the doors of Catholic Relief Services (CRS), an entity of the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB) that enlisted him for donations of food and medicine, which he distributed in refugee camps.

Fr. Fillie has also served many years outside Africa. Now he spends his time thinking of how best to serve the vulnerable people in his village, as well as give back to his Congregation.

From the Spiritans’ house in Kimmage in Ireland, Fr. Fillie takes a bus every Tuesday and Thursday to preside over Holy Mass with the Community of the Poor Clares, some 10 minutes away, and goes back to his Predictive Anthropological research.

The Priest who eats, sleeps, and breathes Anthropology believes that Christianity in Sierra Lone is rooted in the indigenous ways of life of the people.

Fr. John Michael Fillie at St. Mary’s Nursing Home & Hospital, Phoenix Park, Dublin. Fr. Fillie worked at the Hospital as Catholic Chaplain from 2013 to 2021 before he was advised to retire because of his age and the COVID-19 outbreak. Credit: Fr. John Michael Fillie

Fr. John Michael Fillie at St. Mary’s Nursing Home & Hospital, Phoenix Park, Dublin. Fr. Fillie worked at the Hospital as Catholic Chaplain from 2013 to 2021 before he was advised to retire because of his age and the COVID-19 outbreak. Credit: Fr. John Michael Fillie

“I sit and imagine an audience. I research and write a lot then I go out to talk to people, especially the young ones,” Fr. Fillie says.

“There is no other way we can keep that continent holding onto the words of Christ except by using their indigenous perception of who they are and their relationship with the divine being,” the Sierra Leonean Spiritan Priest says, and adds, “Resurrection, for instance, isn’t anything new to us as Africans. We already believe in the life after death.”

He continues, “All we need is to dig deep and find out the beliefs that are helping our people to survive. The people believe in taking care of each other, trusting each other and celebrating together. That is the very basis of Christianity because at some point when Jesus learns that Peter’s mother-in-law is sick, he goes to her immediately.”

Sometimes, Fr. Fillie calls home to find out the progress of land he and his confreres are developing in Niahun village in Southern Sierra Leone: a Technical College to equip youths from vulnerable families with employability skills, and an accommodation facility, which he plans to hand over to members of his Congregation once it is completed.

The Spiritan Priest knows the accommodation challenges of his Congregation in the West African country.

Divulging what he plans to do with the 600 acres of land given to him as his share of family property, Fr. Fillie says, “We have only one house in the whole country; the one in the Diocese of Bo. It has only eight rooms.”

“If twenty Holy Ghost Fathers were to go to Sierra Leone now, they wouldn’t have a place to stay, and we would have to pay for accommodation in other places. That is why I have desired to have a bigger place constructed for the Congregation,” he says in the March 28 interview.

The Spiritan Priest shares that he is planning to go back to his village later this year, and adds, “I have spent many years of my Priesthood in class. Now I want to do more work with my hands. I want to go and grow some crops, do pastoral work, and meet the children in my village where I am the oldest man alive.”

Agnes Aineah is a Kenyan journalist with a background in digital and newspaper reporting. She holds a Master of Arts in Digital Journalism from the Aga Khan University, Graduate School of Media and Communications and a Bachelor's Degree in Linguistics, Media and Communications from Kenya's Moi University. Agnes currently serves as a journalist for ACI Africa.

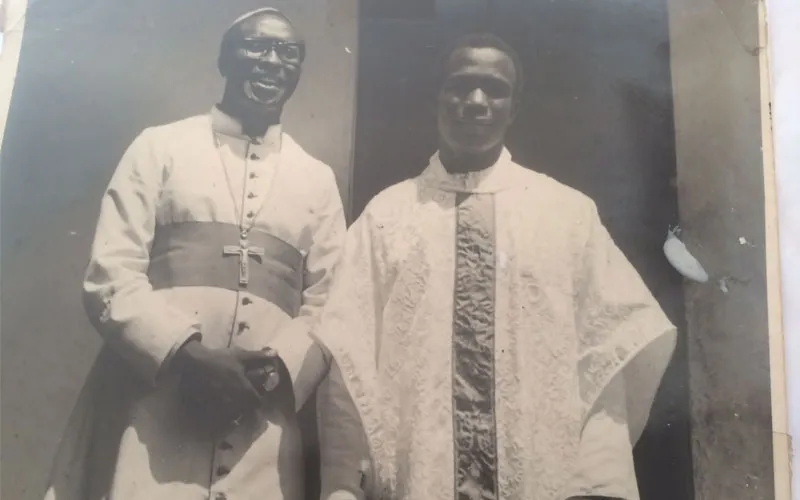

Fr. John Michael Fillie in an undated photo with Archbishop Joseph Henry Ganda, the first Catholic priest in Sierra Leone. Credit: Fr. John Michael Fillie

Fr. John Michael Fillie in an undated photo with Archbishop Joseph Henry Ganda, the first Catholic priest in Sierra Leone. Credit: Fr. John Michael Fillie

Credit: Fr. John Michael Fillie

Credit: Fr. John Michael Fillie Credit: Fr. John Michael Fillie

Credit: Fr. John Michael Fillie Fr. John Michael Fillie at St. Mary’s Nursing Home & Hospital, Phoenix Park, Dublin. Fr. Fillie worked at the Hospital as the Catholic Chaplain from 2013 to 2021 before he was advised to retire because of his advanced age and the COVID-19 outbreak. Credit: Fr. John Michael Fillie

Fr. John Michael Fillie at St. Mary’s Nursing Home & Hospital, Phoenix Park, Dublin. Fr. Fillie worked at the Hospital as the Catholic Chaplain from 2013 to 2021 before he was advised to retire because of his advanced age and the COVID-19 outbreak. Credit: Fr. John Michael Fillie Fr. Peter Konteh. Credit: Caritas Freetown

Fr. Peter Konteh. Credit: Caritas Freetown Fr. John Michael Fillie at St. Mary’s Nursing Home & Hospital, Phoenix Park, Dublin. Fr. Fillie worked at the Hospital as Catholic Chaplain from 2013 to 2021 before he was advised to retire because of his age and the COVID-19 outbreak. Credit: Fr. John Michael Fillie

Fr. John Michael Fillie at St. Mary’s Nursing Home & Hospital, Phoenix Park, Dublin. Fr. Fillie worked at the Hospital as Catholic Chaplain from 2013 to 2021 before he was advised to retire because of his age and the COVID-19 outbreak. Credit: Fr. John Michael Fillie