Here are the five things you probably didn’t know about the South Sudanese prelate who De Schipper describes as “a shepherd and leader who managed to achieve something in war-torn South Sudan that the United Nations had never been able to do.”

A bishop…a mechanic

De Schipper once located Bishop Paride in the bush and found the Bishop standing next to a lorry, carrying work tools and ready to steer the lorry back to motion.

“He gave me an arm, not a hand, because he was holding a fuel pump full of oil,” De Schipper writes, narrating his experience with Bishop Paride.

On a separate day, the author woke up and found the Bishop outside a hut at Kuron Peace village, bending over the bonnet of the episcopal truck, grease on his hands, blowing into a clogged fuel pump.

(Story continues below)

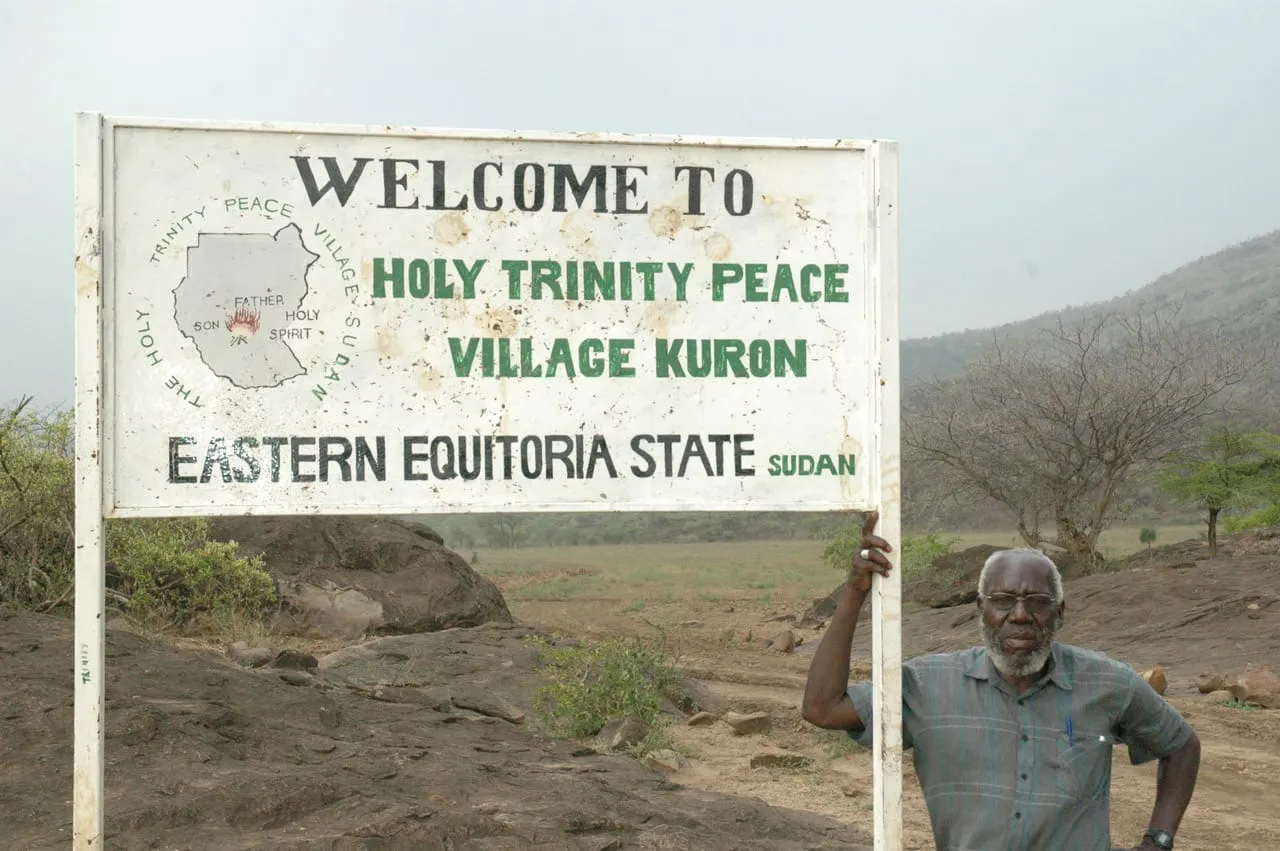

Kuron Peace Village South Sudan. Credit: Paul de Schipper

Kuron Peace Village South Sudan. Credit: Paul de Schipper

Bishop Paride grew up in the town of Torit surrounded by colonial factory workers. His father was one of them. In Seminary, he is said to have learnt how to make furniture and repair cars.

At some point, Paride met Ed Resor of Catholic Relief Services and accepted an invitation to go to the US. There, he worked on Ed’s father’s ranch in Wyoming, where he helped repair fencing and cleaned stables.

In a tribute shared with ACI Africa, De Schipper describes Bishop Paride as “a practical person, a no weak hands prelate.”

Well-dressed missionaries, an inspiration to become a priest

Born in 1936 to a father who was a non-practicing Muslim and a mother who was an adherent of traditional religion, there was no indication that little Paride who went about without pants would become a Catholic Priest.

De Schipper writes that in 1951, young Paride attended the seminary in Okaru “because the missionaries there wore such lovely clothes”.

Sharing his inspiration to become a Priest, Bishop Paride told the author that first, he wanted clothes, and that “faith came later.”

A Bishop with an airfield and a road

De Schipper describes Bishop Paride as “probably the only bishop in the world with his own airfield.”

One day, the Bishop gave De Schipper a ride to the airfield which, according to the author, was later overgrown and left for goats and donkeys to graze on.

There, he saw the excitement of the Bishop who steered his Toyota Land Cruiser onto the start of the airstrip, and cried, “I want to fly.”

De Schipper says that the car’s brakes squeaked “as if a Boeing was landing.”

In 1997 when the war has destroyed all the roads in Taban’s diocese Torit, the Bishop thought that the communities needed connections to one another.

De Schipper writes in his book, “The ‘contractor’ Taban therefore decides to build a road from the Kenyan border to the easternmost part of his diocese, the district of Kuron. The 300-kilometre-long ‘Taban Highway’ is excavated and paved using a bulldozer that the rebels had captured from the government.”

A cross and a furious donkey owner’s shot

In his book, De Schipper mentions the day that Bishop Paride survived by a whisker when an angry donkey owner shot at him, aiming at the chest. In fact, it was a cross that the Bishop wore that shielded him from what would have been a deadly shot.

At 71, Bishop Paride was still in excellent physical condition and drove for hours along routes that were barely passable for cars. The roads were terrible, De Schipper wrote, adding that the Bishop had spent 10,000 euros to get new parts for a single truck in a month.

The worst thing about the impassable roads happened when the Bishop collided with a donkey, killing it accidentally.

“The bishop’s cross on his chest saved him from a fatal shot from the furious owner,” De Schipper said.

Months in a bush prison

On countless occasions as war raged in South Sudan, Bishop Paride put himself on the frontline.

On 31 May 1988, he was part of a food convoy with 100 lorries that left Juba for the famished town of Torit, accompanied by an escort of government soldiers.

“The journey from Juba," the Bishop shared with De Schipper, “became a descent into hell.”

“We were continually being shot at, there were ambushes, the lorries rode over mines. There were one or two fatalities every day.”

Muslims among the soldiers told the Catholic Church leader, “Bishop, pray for us.”

At end of January 1989, De Schipper was the last person that the Bishop spoke to before he was captured by rebels.

Credit: Paul de Schipper

Credit: Paul de Schipper

“Torit fell on 26 February,” the Bishop recounts in De Schipper’s book, and adds, “The rebels captured me. I spent 100 days in a bush prison. On the 25th anniversary of my ordination as a priest, 24 May 1989, they took me to Torit and put me under house arrest. The world thought I was dead. I was only freed one year later.”

Meanwhile, De Schipper has mourned the passing of Bishop Paride who he says offers invaluable lessons for countries experiencing conflict.

According to the Dutch journalist, the Bishop’s life is testimony that “freedom and peace can be learnt.”

“This is the message Paride Taban gives us with Kuron Peace Village, an island of peace functioning as a wonderful, enlightening beacon in a sea of renewed violence and war flaring up,” he says, and adds that the Bishop’s devotedness to freedom and peace sets “an example to us all.”

Agnes Aineah is a Kenyan journalist with a background in digital and newspaper reporting. She holds a Master of Arts in Digital Journalism from the Aga Khan University, Graduate School of Media and Communications and a Bachelor's Degree in Linguistics, Media and Communications from Kenya's Moi University. Agnes currently serves as a journalist for ACI Africa.

Credit: Paul de Schipper

Credit: Paul de Schipper

Kuron Peace Village South Sudan. Credit: Paul de Schipper

Kuron Peace Village South Sudan. Credit: Paul de Schipper Credit: Paul de Schipper

Credit: Paul de Schipper