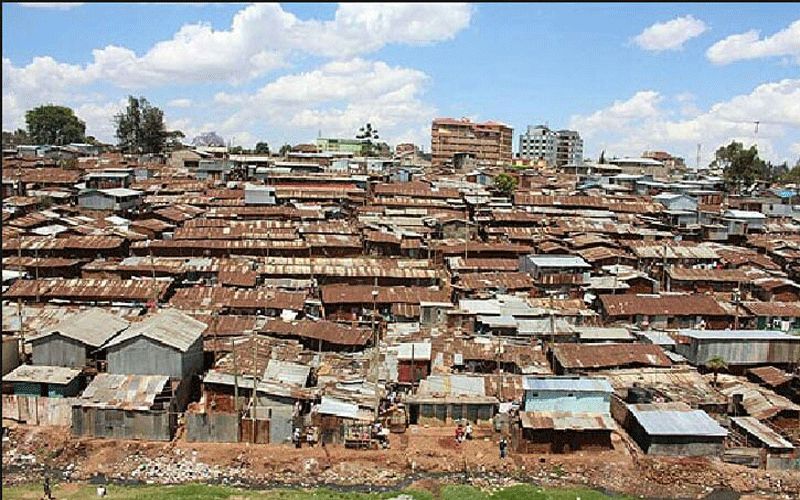

“Here in Mukuru kwa Njenga, people stay close to each other. There are about 20 small houses made of iron sheets in every single apartment and in each single-roomed house, there are about five people staying together. How can these five people in one room maintain social distance?” the Kenyan-born Cleric poses.

He adds, “Staying in these congested rooms all day and night also increases the risk of infection.”

According to the Kenyan born priest, about 100 people in 20 households share a public toilet which also thwarts any efforts for them to observe social distancing.

He says congestion in the slum was made worse when the Kenyan government directed all learning institutions, about three weeks ago, to close and to send learners home.

“There are so many children all packed in the slums. There is no space to breath, let alone a metre or two of social distancing. It is just difficult over here,” says Fr. John.

(Story continues below)

The slum residents who survive on less than a dollar every day pay KES.10 (USD 0.1) for 20 litres of water, which they drink and use for cooking.

Agnes Musyoka, 67, stays with her six grandchildren and a husband who has been paralyzed for 10 years. She told ACI Africa that she struggles to get water to drink and did not care about washing hands.

“When I have money, I buy enough water to even do laundry. But there are days like today, when I lack 10 shillings to buy water to drink,” she says, adding, “I know the importance of washing hands because the government has announced it to us in the media. But for us, water is sometimes a luxury.”

Before businesses started shutting down in Nairobi and a daily curfew, Mrs. Musyoka says she made KES.100 (US$1.00) on a good day from selling bananas.

“I don’t sell bananas anymore. I used to get the bananas from other people that have since closed business. Now I just stay in the house and depend on Fr. John Munjuri’s people who bring us food,” the elderly woman says.

Fr. John has been running a feeding program for the most vulnerable slum dwellers under the auspices of St. Vincent de Paul Group at the parish since 2015.

The group that has identified the neediest cases within Mukuru kwa Njenga and three other surrounding slums distributes food that is collected from all the six parish centers of St. Mary’s Catholic Parish every Sunday.

But the group has been experiencing a decline in the offertory since people stopped going to Church for fear of being infected with the virus.

“People at St. Mary’s Parish stopped going to Church even before the government prohibited social gathering. The other Sunday, those who tried to attend Mass at one of the outstations were chased away by the police. And last Sunday, we didn’t have any offertory collection,” Fr. John says, adding, “We still have very little in our reserve and that’s what we have been distributing to the group members.”

The Spiritan cleric continues, “We don’t know how long we shall keep doing this (giving food to the poor). There is very little remaining and last week, we only gave each family two packets of maize flour, which can only sustain them for two days.”

A majority of the people supported by the St. Vincent de Paul group are infected with HIV and cannot take their medication on an empty stomach, according to Fr. John.

“There are about 28 people who come for food every Friday and 20 of them are HIV positive,” he says, expressing concerns about the impact of undernutrition in the lives of persons living with HIV and AIDs.

According to Maryknoll Fr. Richard Bauer, however, “the vast majority of HIV positive persons in Kenya are now on the new anti-retroviral medicine combination that can be take on a full or empty stomach.”

Fr. Bauer told ACI Africa that “the dietary restrictions are now almost over except for a very small percentage of patients.”

Fr. John expresses another concern with regard to the slum dwellers under his pastoral care. The Kenyan government, he says, has shifted its focus away from chronic diseases in the fight against COVID-19, a situation that Fr. John says has put people with HIV in the slums at the risk of battling opportunistic infections for lack of medication and care at the hospitals.

Veronica Nthenya is one of the volunteers at St. Vincent de Paul who distributes food to beneficiaries of the group who are bedridden. With the increasing infections of coronavirus in the East African country, Veronica foresees a situation where the sick in the slums will be left to their own devices.

“Today and yesterday, my colleagues and I have distributed food to 15 slum residents because they couldn’t come to pick it from the Church premises,” Veronica tells ACI Africa in an interview Tuesday, March 31.

She adds, “We visit the sick without any form of protective gear yet they have very low immunity. We don’t have gloves, masks, we can’t even afford to buy sanitizers. If this situation persists, we might be forced to stop visiting these people in their homes. And I doubt if they will survive without food.”

The St. Vincent de Paul community volunteer appeals to the Kenyan government to supply community health workers with protective gear, a call that Fr. John reiterates, saying, “As the government seeks to support the poor in the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic, let it consider, in a special way, the most vulnerable groups in the slums.”

He adds, “We call on our government leaders to set up water tanks and taps in strategic places within the slums where everybody can wash hands. Let them also use all means possible to ensure that these people get food supplies so that they don’t starve.”

The Kenyan Priest says that plans are underway to set up collection points within the slums where well-wishers can drop food items that can be distributed to the vulnerable slum residents.

Agnes Aineah is a Kenyan journalist with a background in digital and newspaper reporting. She holds a Master of Arts in Digital Journalism from the Aga Khan University, Graduate School of Media and Communications and a Bachelor's Degree in Linguistics, Media and Communications from Kenya's Moi University. Agnes currently serves as a journalist for ACI Africa.