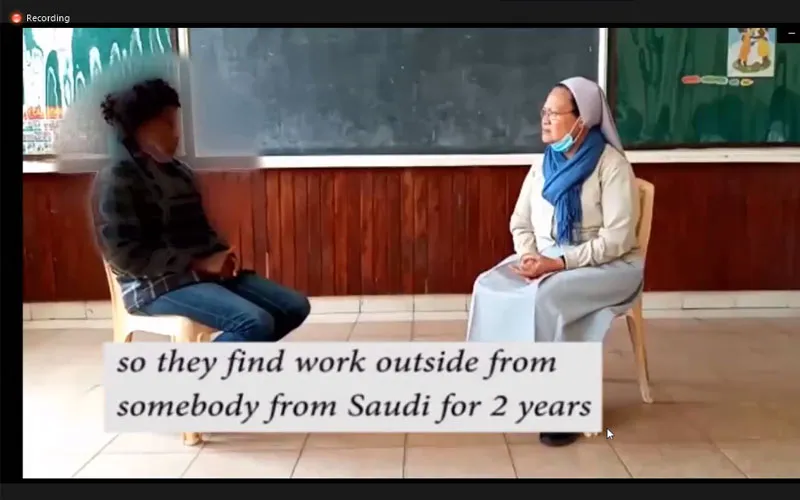

In her presentation at the Thursday, January 7 conference, Sr. Jane Joan Waruguru Kimanthi from the Association of the Sisterhoods of Kenya (AOSK) recalled that lockdown measures that were put in place by governments to limit the spread of COVID-19 provided avenues for exploitation of immigrants in foreign countries.

“The restrictions trapped many people and especially the migrants; those that had been trafficked in different places could not go back to their countries of origin. They were trapped and one can only imagine the many abuses that took place while they were away,” said Sr. Jane Joan.

The high levels of poverty and the financial crisis that many countries plunged in during the COVID-19 pandemic were also catalysts of human trafficking as many people looked for unconventional ways to leave their countries in search for survival, the member of the Sisters of Our Lady of Charity (OLC) said.

(Story continues below)

More than 100 participants logged into the virtual event that was organized by Rome-based Talitha Kum, an organization of Catholic women established by the International Union of Superiors General to end human-trafficking.

Other organizers of the event were Kenyan-based Religious Against Human Trafficking (RAHT) and the Association of the Religious in Uganda (ARU). Organizers also brought on board AOSK and the Religious Superiors Conference of Kenya (RSCK).

In her keynote address on the reintegration of trafficked migrant workers as returnees, Sr. Florence Kisilu, the Chair of Africa Santa Marta Group, which works on the continent to prevent human trafficking and to restore dignity for returnees of human trafficking noted that re-integration of victims is not easy.

“Reintegration is one of the most difficult and complex aspects of assistance to trafficked persons. Meaningful reintegration is complex, costly and very expensive. It requires a full and diverse package of services for the individual and also the family to address the root causes of trafficking as well as the physical, mental and social impacts of their exploitation,” said Sr. Florence during the January 7 virtual event.

According to the member of the Executive Board of the Migrants, Refugees, Seafarers and Human Trafficking Commission of the Kenya Conference of Catholic Bishops (KCCB), victims of human trafficking go through various forms of trauma, which inhibit their reintegration success.

They include chronic health problems, psychiatric problems, lack of self-esteem and motivation in the reintegration process.

She said that victims of human trafficking are physically assaulted, beaten with sharp objects and some are sexually abused “and more than often bear scars and bruises.”

“Many at times, when they return to their home countries, they are traumatized, physically weak and sick and at times their lives are at risk,” the Catholic Nun who also provides professional counselling says, and adds in reference to the returnees, “They move around with self-pity and are stigmatized by the society that associates human trafficking with prostitution.”

Sr. Florence says that reintegration of human trafficking returnees in Kenya is a collaboration between various stakeholders including the police, Justice and Peace departments, immigration and tourism departments, hospitals as well as children offices.

The process takes a multicultural approach, the former Provincial Leader of the Sisters of OLC in Eastern Africa says, noting that apart from being a big source of trafficked individuals, Kenya also hosts people trafficked from other countries.

In April, Police in Kenya reportedly rescued 29 women who were suspected victims of human trafficking after they were abandoned by recruitment agents due to COVID-19-related travel restrictions.

This came after reports emerged of 96 Ugandans, mostly children and youth, were intercepted in Kenya, while on their way to the United Arab Emirates. The girls aged between 14 to 18 years were intercepted at JKIA in Nairobi where they were due to board their next flight to the Emirates.

Concerned about the situation of human trafficking in the Middle East, U.S. congressmen signed a letter to the U.S. government calling for an end to human trafficking and labor exploitation in the Gulf region of the Middle East.

Signed by 30 congress members, the letter stated, “In Saudi Arabia, the Kafala system (modern slavery) ensures that a migrant worker cannot leave the country without permission from their sponsor, paving the way for exploitative practices.”

According to the U.S. lawmakers, the government continues to “fine, jail, and/or deport migrant workers for prostitution or immigration violations”, pertaining to cases of unidentified victims of labor or sex trafficking.

Church-affiliated organizations and individuals working to prevent human trafficking and to restore dignity in returnees were also recognized at the five-hour virtual conference.

These included Kenyan-based Solidarity with Girls in Distress (SOLGIDI), a Caritas programme in the Catholic Diocese of Mombasa, which works with families of female commercial sex workers “to give them back the missed opportunities in life.”

At the height of COVID-19 pandemic in Kenya, SOLGIDI provided food relief to their beneficiaries and supported the group, which is sidelined by society with stipends to weather the COVID-19 storm.

Others were Counter Human Trafficking Trust-East Africa (CHTEA), a regional non-state agency, which is dedicated to the elimination of human trafficking; Awareness Against Human Trafficking (HAART) Kenya, which continues to provide emergency support to survivors of human trafficking; and the Loreto Sisters whose COVID-19 response alleviated suffering in informal settlements around Kenya’s capital, Nairobi.

Agnes Aineah is a Kenyan journalist with a background in digital and newspaper reporting. She holds a Master of Arts in Digital Journalism from the Aga Khan University, Graduate School of Media and Communications and a Bachelor's Degree in Linguistics, Media and Communications from Kenya's Moi University. Agnes currently serves as a journalist for ACI Africa.