A Theologian, Mr. Torres who hails from Spain has worked for 20 years in Africa in collaboration with the Catholic Church and with several other faith-based and secular organizations.

Mr. Torres has been the Director of Radio Wa, a community radio owned by Uganda’s Catholic Diocese of Lira.

In the essay shared with ACI Africa on August 1, Mr. Torres noted that with the independence of South Sudan in July 2011, the people thought that they had put their days of turmoil behind them. This, according to the author, was, however not the case.

“The 9th of July of 2011 marked for millions of people the start of a new era,” Mr. Torres said.

He explained, “After very long years of incommensurable suffering caused by discrimination, resentment and civil war, after signing a laborious peace agreement that put an end to the longest armed conflict in Africa, it looked that the voice of the Southern Sudanese finally be heard and people there would not only experience peace and security, but also they would be able to enjoy a new country on their own, with their own elected leaders, with functioning and fair institutions, and with the perspective of a new life in harmony, respect and social justice.”

(Story continues below)

Mr. Torres added, “The great hopes and expectations of 2011 have now radically sobered up, and in many cases they are now completely dashed.”

The author expresses regret that violence, human rights violations, displacement, and ethnic strife are again commonplace in the country with the “shameless complacency” and the “disgraceful passivity of a corrupt ruling elite.”

He notes that more than ten years after independence, there has not been any relevant change on the top leadership in South Sudan.

“The former-freedom-fighters-now-rulers have remained glued to their positions of power and show no intention of handing over their offices to younger, better prepared and more qualified candidates. To make matters worse, they keep following the warlord playbook,” Mr. Torres says.

He decries the lack of press freedom in South Sudan, noting that media outlets in the country have been curbed and outspoken journalists are threatened or incarcerated if they expose any inconvenient truth that diverts from the official version of things.

He says that there is little hope for a better leadership in the country’s forthcoming elections, adding, “As a result of all these factors, millions of citizens have their livelihoods threatened by political games and they live in constant fear for their lives.”

According to the essayist, South Sudan hardly has any leading figures able to stand up to corrupt leaders and call political and social leaders to account.

“Most dissidents or critical elements of the civil society have either been silenced or had to leave the country. Moral authority is presently the most needed commodity in the Southern Sudanese social fabric,” Mr. Torres says.

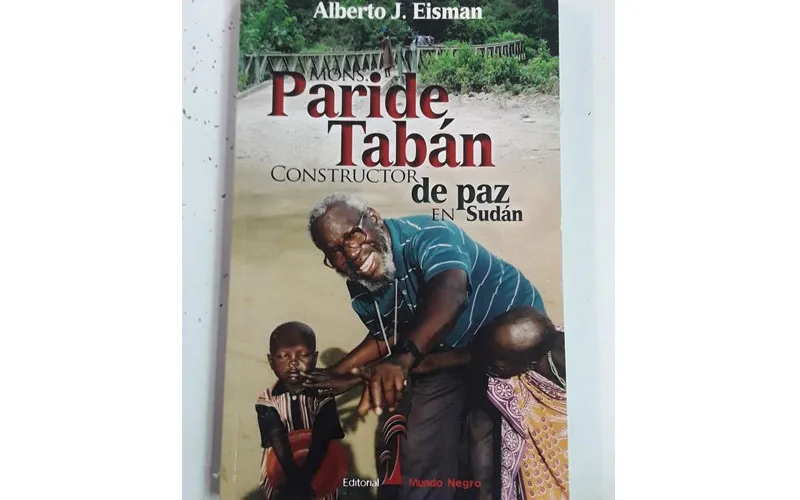

Amid the challenging South Sudanese situation, Bishop Paride’s Holy Trinity Kuron Peace Village, a facility he founded in 2005 to bring healing between warring tribes in South Sudanese, has become “a peace-building vision made reality,” according to Mr. Torres.

The village that is situated in South Sudan’s State of Eastern Equatoria, Mr. Torres says, has already transformed and improved the lives of thousands of people around that area.

The Holy Trinity Kuron Peace Village, according to Mr. Torres, is an initiative that “most boldly incarnates Paride’s vision of fraternity and peaceful coexistence.”

The Peace Village had an encounter center where representatives of warring tribes meet and discuss issues related to their conflicts and differences. There is a dispensary and a school which, according to Mr. Torres, enhance the variety of social services available at the Peace Village.

There is also a wide strip of land meant for agricultural activities where families, who only relied on cattle rearing in the past, now grow crops to supplement their food sources.

Many beneficiaries, the author says, have already discovered the value of agriculture as a means of life and, as a result, they have settled down in the vicinity of their fields instead of being itinerants running after the cattle.

Some young people from the region, particularly girls, now have educational opportunities that had eluded them, Mr. Torres narrates, adding that a new Secondary School has been opened in the area and local youth are now able to prepare themselves for higher education, “something unthinkable only some few years ago.”

“Apart from providing services to the community, the place remains a sanctuary for those who want to opt for a peaceful way of dealing with each other. Though cattle rustling is still present in the region, the Peace Village is already presenting concrete alternatives and a forum to defuse tensions and mitigate the effects of such a practice,” Mr. Torres says about Kuron peace village that Bishop Paride founded a year after he retired from the pastoral care of the Catholic Diocese of Torit in 2004 aged 68.

He adds, “Kuron is a peace-building vision made reality. By implementing it; Bishop Paride literally became a pontiff, a bridge-builder not only between unconnected river banks, but also between foes and adversaries.

Agnes Aineah is a Kenyan journalist with a background in digital and newspaper reporting. She holds a Master of Arts in Digital Journalism from the Aga Khan University, Graduate School of Media and Communications and a Bachelor's Degree in Linguistics, Media and Communications from Kenya's Moi University. Agnes currently serves as a journalist for ACI Africa.